Huertas de Datos: Open Referral en Madrid

Artículo original en inglés Huertas de Datos: Open Referral in Madrid, por Greg Bloom

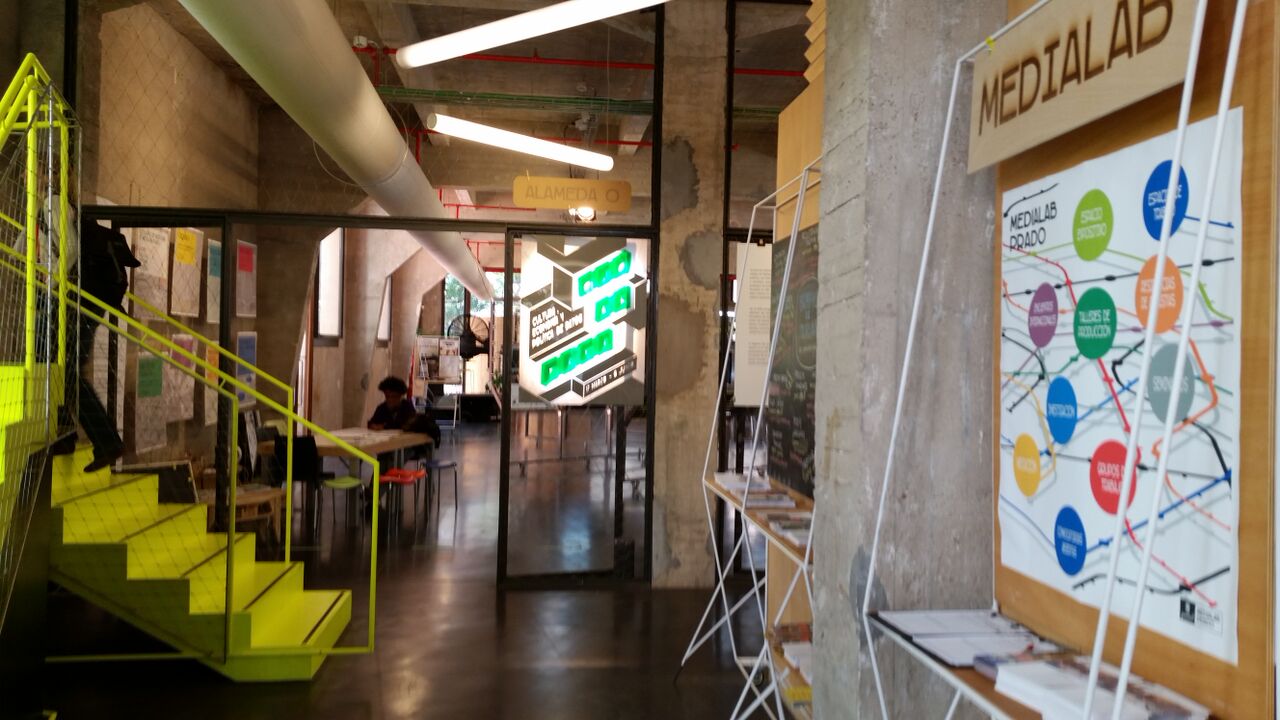

El pasado mes (se refiere a abril), viajé a Madrid para participar en un debate sobre el problema dispersión de la información relativa a los sistemas de atención socio-sanitaria y el trabajo que desde la iniciativa Open Referral (Servicios de atención socio sanitarias Abiertos) estamos realizando, al comienzo del taller Visualizar15 en Medialab-Prado.

Medialab-Prado es un “laboratorio ciudadano para la producción, investigación y desarrollo de proyectos culturales que exploran formas colaborativas de experimentación y aprendizaje que emergen a partir de las redes digitales”, un centro cultural público del Ayuntamiento de Madrid.

Y también es un lugar precioso

Staircase via http://we-make-money-not-art.com/

Staircase via http://we-make-money-not-art.com/

Este año el taller Visualizar15 llevaba por tema “el procomún de los datos” o “commoning data”, por lo que no podía dejar pasar esta oportunidad de dar a conocer el proyecto.

En Open Referral nos hemos referido ocasionalmente a los comunes en el curso de nuestro trabajo, pero sobre todo en mi ensayo sobre “Code for America’s Beyond Transparency” (más allá de la transparencia de código para América): “Hacia el común de los datos comunitarios”, lo cual, de alguna manera, motivó la iniciativa Open Referral. En este ensayo, discuto sobre cómo el verdadero significado de los comunes va mucho más -y, creo que algunas veces distorsiona- el típico uso asociado actualmente con “datos abiertos” e Internet en general.

Demasiado a menudo, se utilizan los comunes para referirse ampliamente a las coas que son libres de uso y gratuitas para cualquiera. Esto es simplificar mucho e incluso equivocarse en lo que se quiere decir.

Prefiero sin duda la descripción de David Bollier sobre los comunes:

Los comunes emergen allí donde una comunidad decide cómo manejar unos recursos de manera colectiva, con especial énfasis por el acceso equitativo, uso colectivo y sustenibilidad

Con ese fin, el taller instaba a sus participantes no solo a ofrecer o demandar datos abierto, sino también ir más allá y desarrollar procesos colectivos para la limpieza, validación y administración de datos abiertos como recurso compartido, algo que debe cuidarse de cara a conseguir su cometido como material que constituya la infraestructura digital de una verdadera sociedad civil democrática.

Creo que este marco nos acercamos con mucha naturalidad a nuestro dilema de directorio de datos de recursos comunitarios. Aquí está el vídeo de mi charla:

</embed>

(To be continued)

After my talk, during discussions with the leadership of Medialab-Prado and other workshop participants, a number of people said to me something like: “Your talk was interesting, but I don’t think we have this problem in Spain. If we need help, either we go to our doctor or to the Administration [the municipal government office] — they can just connect us to anything.”

It does seem like the service sectors in Spain are mostly organized around the state, with (broadly speaking) health services provided by regional government and human services provided by municipalities.

Surely enough, however, once we ventured outside of the Medialab to discuss with people in the field, the familiar problems emerged.

Many services are provided by many different government agencies, and even government staff find it challenging to know what is happening where.

Spain even has numbers for non-emergency assistance — most prominently 010 in municipalities and 012 in regions, similar to North America’s 3-1-1s and 2-1-1s — as well as specialized assistance lines such as 016 for survivors of domestic violence. People I spoke with reported decidedly mixed experiences in terms of the ability for information to travel effectively among these call-center services.

Meanwhile, services for marginalized populations — undocumented immigrants, elderly, homeless, mentally ill — are increasingly provided by non-profit organizations, which lack any reliable means of sharing directory information. During a couple of visits to the Fundación San Martin de Porres, I heard their staff describe various service directory projects that they have struggled to implement (such as the ‘Recursos’ page of a public-facing homelessness website, Noticiaspsh.org).

(When I relayed these results to some of the participants who had expressed doubts about whether this is really a problem in Spain, one replied: “huh, perhaps this just shows how ‘W.E.I.R.D.’ we really are” — referencing the acronym of ‘white educated industrialized rich and democratic’ from a recent paper about the biases of people in Western countries who participate in research, policymaking, etc.)

The Commoning Data workshop ran two full weeks (though I was only able to stay for the first couple of days). At the start of the workshop, people self-organized into different projects — including the ‘CityAPI’ group, which was focused upon making data from Madrid’s Open Data Portal accessible via API. Within the CityAPI group, Amanda Sorribes (a PhD student in quantitative neuroscience who came to the workshop hoping to put her data crunching skills to use for the greater good of society) decided to explore the community resource directory data problem.

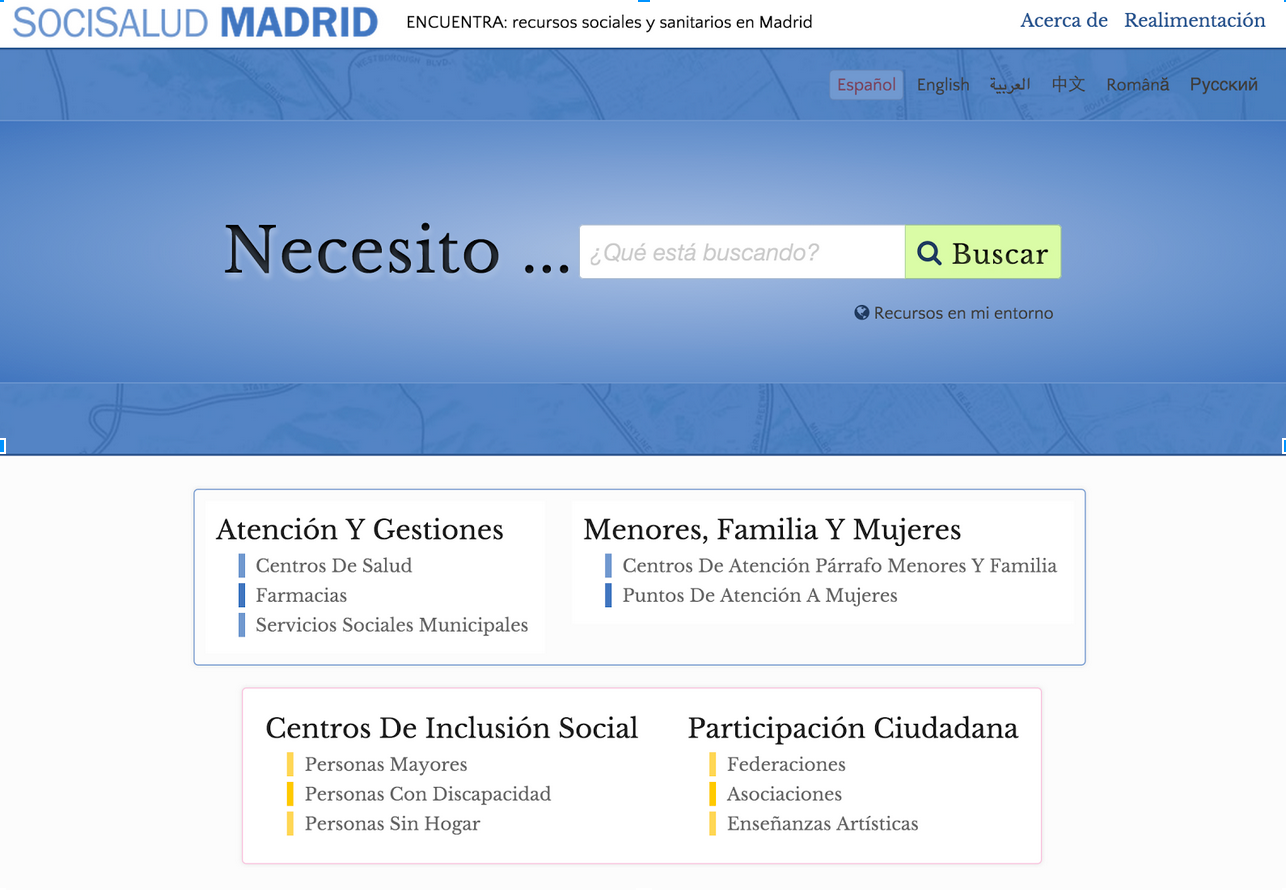

After spending just a couple of minutes on Madrid’s open data portal, we found what we were looking for: quick searches for ‘recursos’ and ‘servicios’ (Spanish for resources and services) turned up a number of directory datasets that appeared to be clean and complete. Over the course of the rest of the workshop, Amanda — along with other Medialab-Prado collaborators including Adolfo Antón Bravo, Gabriel Lucas, Álvaro Santamaría, and Lorena Ruiz — managed to translate the Open Referral format and Ohana API, convert several directory datasets into the former and load them into the latter, deploy the Ohana Web Search front-end, and customize it for Madrid.  And so, an Open Referral demonstration emerged in Spain!

And so, an Open Referral demonstration emerged in Spain!

The excellent work done by Amanda and her collaborators, of course, amounts to only the first step in what will be a long path towards a robust resource directory ecosystem. The ‘SociSalud Madrid’ website, frankly, is unlikely to solve anyone’s problems just yet; it merely provides us with a glimpse of possibility for new kinds of solutions.

Many issues have yet to be explored: what is the government’s plan for maintaining those directory datasets on its Open Data Portal? Are there important services that haven’t been published on the portal, or perhaps aren’t even being monitored by the government? How can publicly-funded services be aggregated alongside data about non-profit services? How could regular users suggest corrections and additions to this information? Who should be responsible for stewarding these data resources over time? These are just some of the questions that must be addressed in the process of ‘commoning’ this critical data.

Medialab-Prado is an ideal site to initiate this inquiry. I look forward to hearing about their progress in the near future!